ÉDOUARD GLISSANT

La Lézarde

The Ripening

“Car c’est

d’un pays qu’il s’agit là, et non pas d’hommes sans raisons. Histoire de la

terre qui s’éveille et s’élargit. Voici la fécondation mystérieuse, la douleur

nue.” (18)

“Here was not just a group of unreasonable men but a country waking up and flexing its muscles. This earth was a scene of a mysterious fecundation, of a naked sorrow.” (18)

La Lézarde, originally published in 1958, is Martinican philosopher Édouard Glissant’s first novel. It tells the story of Thaël, a young descendant of maroons, who travels to the low-lying town of Lambrianne to carry out the political assassination of a renegade named Garin.

While the novel can be read as a political drama, a bildungsroman, and a love story, it might also be labeled a novel of landscape. Glissant has argued elsewhere that landscape must be understood as an active character in the making of Caribbean histories rather than as a passive backdrop to their unfolding. In La Lézarde, the current of the eponymous river propels the story downward from the mountains to the plains to the river delta where it meets the sea, revealing the ever-changing tapestries of human and vegetal life along its banks. Indeed, the novel suggests that the ripening of the tropical vegetation precipitates the ripening collective will for political autonomy among the young people of Lambrianne.

While the novel can be read as a political drama, a bildungsroman, and a love story, it might also be labeled a novel of landscape. Glissant has argued elsewhere that landscape must be understood as an active character in the making of Caribbean histories rather than as a passive backdrop to their unfolding. In La Lézarde, the current of the eponymous river propels the story downward from the mountains to the plains to the river delta where it meets the sea, revealing the ever-changing tapestries of human and vegetal life along its banks. Indeed, the novel suggests that the ripening of the tropical vegetation precipitates the ripening collective will for political autonomy among the young people of Lambrianne.

Three trees serve as landmarks along Thaël’s journey: a flamboyant, a prunier moubin (hog plum), and a fromager (ceiba or silk-cotton tree). This triad of imported and native trees encloses the novel in an arborescent palindrome, appearing in order at its outset when Thaël descends the mountain and then in reverse when he climbs back up at its conclusion. The trees help him make sense of his surroundings, but they also threaten those uninitiated in local medicine; the shade of the hog plum tree, for instance, is refreshing to hikers on the descent but dangerously sickening to those climbing the slope back up from the valley floor.

Thaël, a montagnard or mountain-dweller, is well-versed in the uses and the perils of the plants of the tropical rainforest. Yet the people he meets in the plains have a different set of experience pertaining to the cultivation and processing of sugarcane. When Thaël falls in love with a woman from the village and attempts to bring her back to his home on the mountain, the gap between their separate spheres of plant knowledge will doom their budding romance.

Thaël, a montagnard or mountain-dweller, is well-versed in the uses and the perils of the plants of the tropical rainforest. Yet the people he meets in the plains have a different set of experience pertaining to the cultivation and processing of sugarcane. When Thaël falls in love with a woman from the village and attempts to bring her back to his home on the mountain, the gap between their separate spheres of plant knowledge will doom their budding romance.

World origins of plant biodiversity in Glissant’s La Lézarde by raw number of species

Arrows highlight the diverse origins of the flora in the novel.

Click on a realm to

explore the plants.

Click again to deselect.

How was this data collected?

World origins of plant biodiversity in Glissant’s La Lézarde weighted by number of mentions

Arrows show the five most mentioned plants in the novel.

Click on a realm to

explore the plants.

Click again to deselect.

How was this data collected?

Percentage of species native to Martinique in Édouard Glissant’s La Lézarde

Native species are mentioned proportionally less than non-native species.

Reflections

Neotropical plants contribute by far the greatest diversity of species to the novel’s botanical imaginary, originating more than twice the number of plants of any other biogeographic realm.

Yet Indomalayan, Australasian, and Afrotropical cultivars are overrepresented in the novel, receiving more mentions than their meager numbers would suggest. This is largely the result of sugarcane (an Australasian and Indomalayan species) receiving 34 mentions, more than twice the number of any other plant species. It dominates the landscape of the plains outside of Lambrianne as well as the imaginary of the people living there. The flamboyant tree, hailing from Madagascar, accounts for the overrepresentation of the Afrotropical realm.

Yet Indomalayan, Australasian, and Afrotropical cultivars are overrepresented in the novel, receiving more mentions than their meager numbers would suggest. This is largely the result of sugarcane (an Australasian and Indomalayan species) receiving 34 mentions, more than twice the number of any other plant species. It dominates the landscape of the plains outside of Lambrianne as well as the imaginary of the people living there. The flamboyant tree, hailing from Madagascar, accounts for the overrepresentation of the Afrotropical realm.

Although sugarcane features heavily in all three texts I have investigated for this project, Glissant’s novel is unique in that three of its top five most mentioned plants are non-cash crops. Ceiba, hog plum, and flamboyant trees are valued for their medicinal, spiritual, decorative, and in the case of the hog plum, culinary properties, but they are not generally cultivated for money. While none of these trees can compete individually with sugarcane in terms of number of mentions, together, they outnumber the Melanesian grass. In foregrounding these lesser known species, Glissant emphasizes the vibrancy of the plant world outside of monoculture sugar fields, whose sameness he associates with brutal working conditions and political oppression.

Learn about the plants in the text that come from each of the world’s biogeographic realms:

Afrotropical realm

Australasian realm

Indomalayan realm

Nearctic realm

Neotropical realm

Palearctic realm

Image credits:

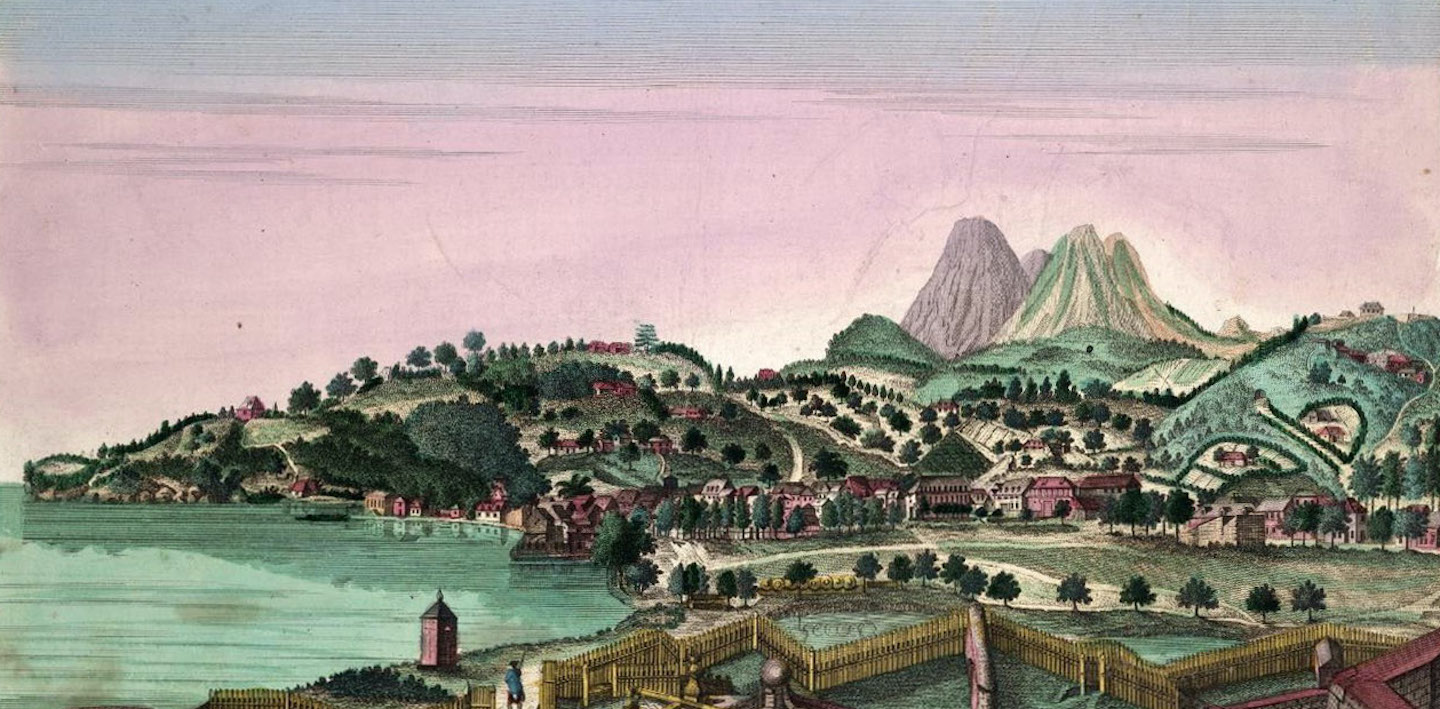

François Denis, Vue Du Fort Royal de La Martinique, circa 1750-1760

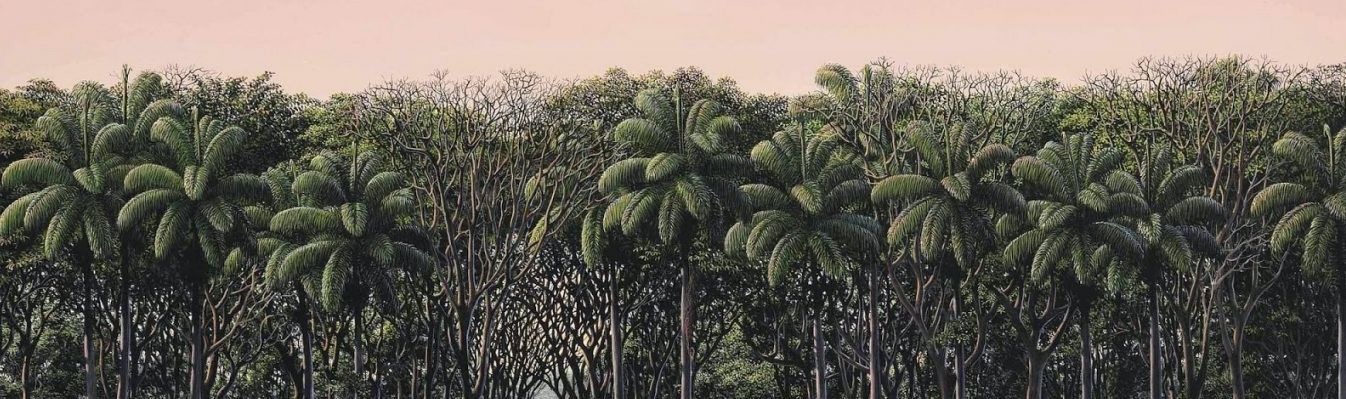

Tomás Sánchez, Autorretrato En Tarde Rosa, 1994, Acrylic on linen, 1994,

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/03/tomas-sanchez-landscape-paintings/.

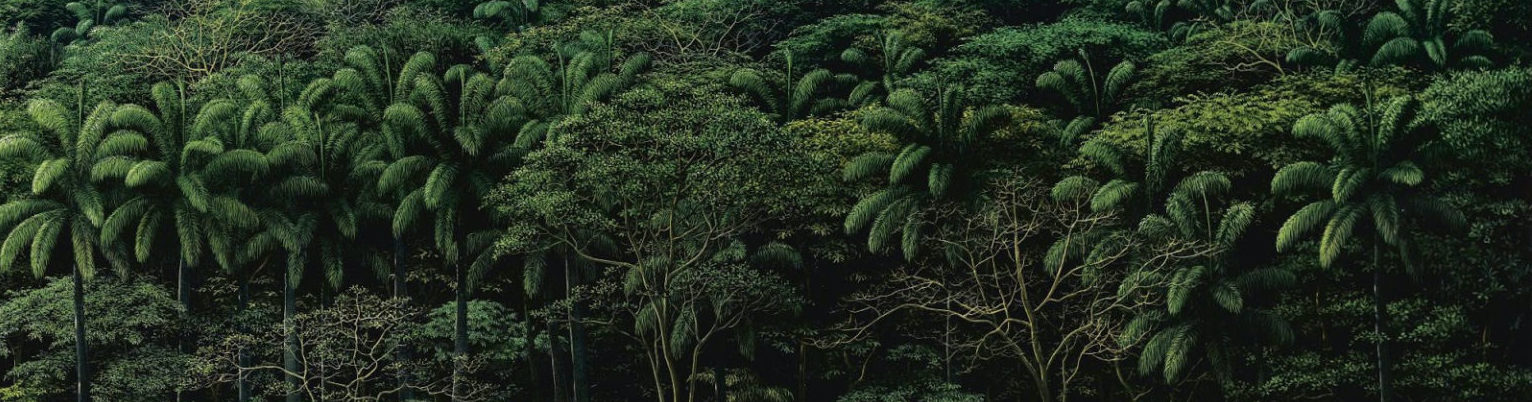

Tomás Sánchez, Orilla y Cielo Gris, 1995, Acrylic on canvas, 1995,

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/03/tomas-sanchez-landscape-paintings/.

François Denis, Vue Du Fort Royal de La Martinique, circa 1750-1760

Tomás Sánchez, Autorretrato En Tarde Rosa, 1994, Acrylic on linen, 1994,

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/03/tomas-sanchez-landscape-paintings/.

Tomás Sánchez, Orilla y Cielo Gris, 1995, Acrylic on canvas, 1995,

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/03/tomas-sanchez-landscape-paintings/.

Text editions:

Édouard Glissant, La lézarde: roman (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1958).

Édouard Glissant, The Ripening, trans. Frances Frenaye (New York: G. Braziller, 1959).