EARL LOVELACE

Salt

“‘Watch the landscape of this island,’ he began with the self-assured conviction that my mother couldn't stand in him. ‘And you know that they coulda never hold people here surrendered to unfreedom.’” (5)

-Uncle Bango

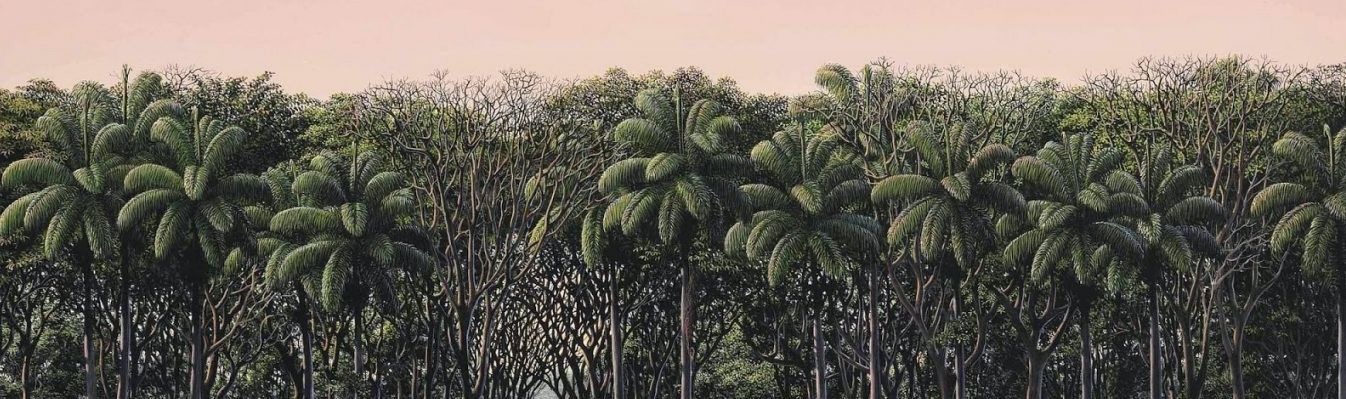

Michael Jean Cazabon, “Caroni River, Trinidad”

Earl Lovelace’s 1996 novel Salt is a multi-generational tale of a Trinidadian family’s struggle for land ownership and dignity in the wake of emancipation. Alford George, the novel’s protagonist, is born to tenant farmers living under the shadow of a giant immortelle tree. Although the tree sickens his mother, the family is forbidden by their landlord from cutting it down. It is not until Alford has grown into a young man and his mother has died that he can save enough money to purchase the plot and dislodge the offending tree.

Thus, certain imported species like the immortelle serve as markers of the bygone system of plantocracy whose roots the characters struggle to deracinate from the soil, while other plants are material signs of Trinidad’s multicultural history. Indentured Indian laborers and their descendants eat geera (cumin), baigan (eggplant), and chaitaigne (breadnut); meanwhile, African grasses speak to the dark legacy of the Middle Passage and its botanical hitchhikers.

Thus, certain imported species like the immortelle serve as markers of the bygone system of plantocracy whose roots the characters struggle to deracinate from the soil, while other plants are material signs of Trinidad’s multicultural history. Indentured Indian laborers and their descendants eat geera (cumin), baigan (eggplant), and chaitaigne (breadnut); meanwhile, African grasses speak to the dark legacy of the Middle Passage and its botanical hitchhikers.

Indeed, the landscape of the novel is dominated by foreign species. Homes are built with invasive East Asian bamboo; “coconutmen” sell the Malesian fruit along the streets of Port of Spain; cocoa farmers prepare the South American commodity for export.

The geographic diversity of the plant species in the novel speaks to its thematic emphasis on Trinidad’s multicultural society. When Alford George first becomes a politician, he advocates a colorblind politics, advising his constituents to see past their historical differences in favor of a unified Trinidadian identity. Yet as he matures, he realizes the necessity of reckoning with one’s own family legacy. Once the immortelle has been uprooted from the family plot, collective acts of ritual take the place of the foreboding tree to keep ancestral memory alive.

The geographic diversity of the plant species in the novel speaks to its thematic emphasis on Trinidad’s multicultural society. When Alford George first becomes a politician, he advocates a colorblind politics, advising his constituents to see past their historical differences in favor of a unified Trinidadian identity. Yet as he matures, he realizes the necessity of reckoning with one’s own family legacy. Once the immortelle has been uprooted from the family plot, collective acts of ritual take the place of the foreboding tree to keep ancestral memory alive.

World origins of plant biodiversity in Earl Lovelace’s Salt by raw number of species

Arrows highlight the diverse origins of the flora.

Click on a realm to

explore the plants.

Click again to deselect.

World origins of plant biodiversity in Earl Lovelace’s Salt weighted by number of mentions

Arrows show

the six most mentioned

plants.

Click on a realm to

explore the plants.

Click again to deselect.

Percentage of species native to Trinidad in Earl Lovelace’s Salt

Native species are mentioned proportionally less than non-native species.

Learn about the plants in the novel that come from each of the world’s biogeographic realms:

Reflections

A wide geographic range of plants appears in the novel, both in terms of raw number of species and in terms of plant mentions.

While 24% of the plants in the novel are native to Trinidad, only 14% of mentions refer to those plants, meaning that non-native plants show up disproportionately often in the text, while native plants are typically mentioned only once or twice. Several non-native Neotropical plants such as cacao and immortelle contribute to this trend, as do Indomalayan, Australasian, and Palearctic cultivars including bamboo, sugar, coconut, and banana.

While 24% of the plants in the novel are native to Trinidad, only 14% of mentions refer to those plants, meaning that non-native plants show up disproportionately often in the text, while native plants are typically mentioned only once or twice. Several non-native Neotropical plants such as cacao and immortelle contribute to this trend, as do Indomalayan, Australasian, and Palearctic cultivars including bamboo, sugar, coconut, and banana.

Image credits:

Michel Jean Cazabon, Caroni River, Unknown, Pencil, watercolor, and gouache on paper, Unknown.

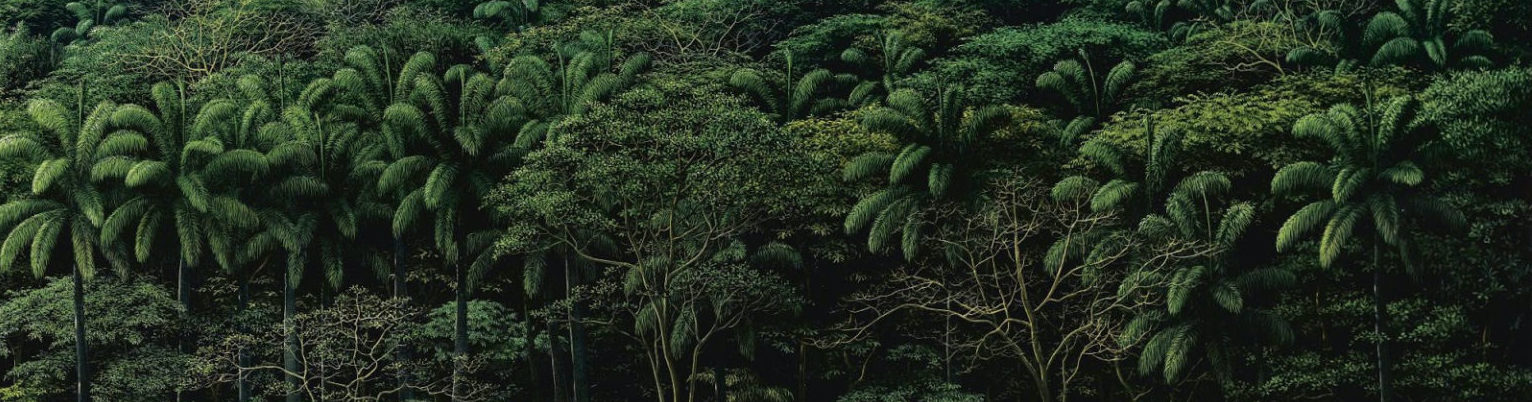

Tomás Sánchez, Autorretrato En Tarde Rosa, 1994, Acrylic on linen, 1994,

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/03/tomas-sanchez-landscape-paintings/.

Tomás Sánchez, Orilla y Cielo Gris, 1995, Acrylic on canvas, 1995,

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/03/tomas-sanchez-landscape-paintings/.

Michel Jean Cazabon, Caroni River, Unknown, Pencil, watercolor, and gouache on paper, Unknown.

Tomás Sánchez, Autorretrato En Tarde Rosa, 1994, Acrylic on linen, 1994,

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/03/tomas-sanchez-landscape-paintings/.

Tomás Sánchez, Orilla y Cielo Gris, 1995, Acrylic on canvas, 1995,

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2020/03/tomas-sanchez-landscape-paintings/.

Text edition:

Earl Lovelace, Salt (New York, 1996),

https://www.proquest.com/books/salt/docview/2138588739/se-2?accountid=10267.

https://www.proquest.com/books/salt/docview/2138588739/se-2?accountid=10267.